The Dance in Morenz’s Game

Did you ever see fire dancing on ice? Have you ever flown into the eye of a hurricane? Did you ever see Pavlova or Nijinsky? No I realize that you know nothing of these things so there’s no point in attempting to describe Howie Morenz to you. . . .

(Jim Coleman, Calgary Herald, February 19, 1971, p.47, c.1 – 2. This assessment is also referenced in Gzowski, Peter; The Game of Our Lives, Heritage House Publishing Ltd. (Surrey, BC: 2004), at p.118)

When Howie first saw Ruby Keeler tap-dancing at the Biltmore Hotel that night he opened the new Madison Square Garden in December 1925, she had looked as young as the schoolgirls he had known in Stratford. The Montreal Daily Star, October 15, 1930, p.35, c.5 suggested that the location of that 1925 encounter with Keeler was in a more intimate space, at one of Texas Guinan’s New York clubs, rather than the Biltmore.

It had been a time when, according to Dorothy Parker in The New Yorker magazine, professional hockey players were regarded as sexually exotic entertainment for the city’s most important women: The New Yorker, August 25, 1928; also quoted in Meade, Marion; Bobbed Hair and Bathtub Gin, Nan A. Talese / Doubleday (New York:2004), at pp.216, 322.

Howie might have been surprised when he discovered, perhaps later than that December 1925 evening, that Ruby had been just 16 then. Even as the critics complained that Keeler’s Irish Step-dance presentation was technically poor, Howie knew from watching her that as a dancer and as a performer, this fellow Canadian from Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, was a kindred spirit. Like himself, she already had enduring, New York City quality, performance skills. Like himself she had never spent a single show in a facelss chorus line. She was the dancer you remembered.

By the time that Ruby was introduced to Howie Morenz, she had already danced her way into the imaginations of countless, tempted hearts. Ruby had been starleted on the nightclub/speakeasy circuit from the age of 13, with her main stage being at the El Fey Club on West 45th under the tutelage and direction of Texas Guinan: Marlow-Trump, Nancy; Ruby Keeler: A Photographic Biography, McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers (Jefferson, N.C.:1998), at p.21; Goldman, Herbert G.; Jolson: The Legend Comes to Life; Oxford University Press (NewYork: 1988), at p.157. Guinan of course also owned Le Cabaret Frolic on Montreal’s St Laurent Boulevard, with Lou Hill as her on-site manager there. Le Cabaret Frolic was one of Howie’s regular hangouts in Montreal: Gzowski, Peter; The Game of Our Lives, McClelland and Stewart Limited (Toronto:1981), at p.124.

It wasn’t only the Guinan connection that suggests the interest here. The common Canadian birthright of Morenz and Keeler would have provided them with a perfect ice-breaker. Both enjoyed singing, and both played the ukulele: Marlow-Trump, Nancy; Ruby Keeler: A Photographic Biography, McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers (Jefferson, N.C.:1998), at p.22.

Keeler was just as athletic as Morenz. As a dancer, her last professional appearance came in a New York revival of No, No, Nanette in 1971, when she was 62 – a revival that played over 800 performances. She also showed off her athleticism in an accomplished golf game: Marlow-Trump, Nancy; Ruby Keeler: A Photographic Biography, McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers (Jefferson, N.C.:1998), at p.122; Goldman, Herbert G.; Jolson: The Legend Comes to Life; Oxford University Press (NewYork: 1988), at p.219.

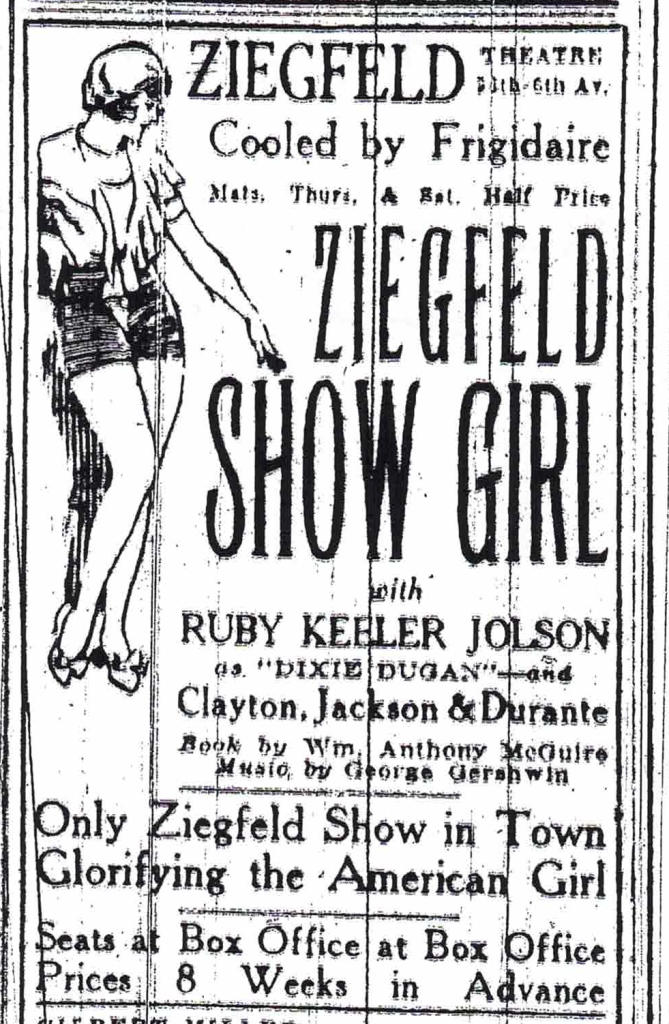

All of that might have allowed him to believe, if only during the time when they saw each other at the Biltmore, or a Guinan club, that he had caught her interest. While the two of them might have made a match, or just a date, at 16 she was probably already out of his league. Keeler’s career had already shifted from the clubs onto the stages of Broadway. She had been a headliner in George M. Cohan’s The Rise of Rosie O’Reilly in 1923; in Charles Dillingham’s Lucky, and The Sidewalks of New York, both 1927; Flo Ziegfeld’s Whoopee in 1928, and Show Girl in 1929.

She had already been dating the famous, like popular jazz musician Bix Biederbecke: Sudhalter, Richard M., and Evans, Philip R.; Bix: Man & Legend, Quartet Books (London: 1974), at p.210. (See Chapter 28 in this Part for a fuller treatment of Bix Biederbecke, and hockey jazz).

She had also been linked with the infamous, like her main guy, gangster Johnny “Irish†Costello, who was one of bootlegger Owney Madden’s men: Goldman, Herbert G.; Jolson: The Legend Comes to Life; Oxford University Press (New York: 1988), at pp.157 – 158. When it was clear that he couldn’t compete with Al Jolson’s million dollar offer for Keeler’s hand in marriage, Johnny apparently ran effective interference to protect her and her new husband from underworld retribution at having dropped him: Goldman, Herbert G.; Jolson: The Legend Comes to Life; Oxford University Press (NewYork: 1988), at pp.162 – 163.

In 1928, at the age of 19, she had accepted Al Jolson’s offer of marriage, and a guaranteed million dollars of his money: Goldman, Herbert G.; Jolson: The Legend Comes to Life; Oxford University Press (NewYork: 1988), at pp.164, 184 – 185. The New York Times, July 14, 1929, advertised that Ruby Keeler Jolson was going to appear at the Ziegfeld Theatre in “Ziegfeld Show Girl.†She left this show apparently for health reasons the same month: Goldman, Herbert G.; Jolson: The Legend Comes to Life; Oxford University Press (NewYork: 1988), at pp.185 – 186, 189 – 193. Jolson proved publicly jealous of the independence of her success. She would soon embark upon a successful film career in Hollywood.

So in December 1930, Keeler wasn’t even in New York very often anymore. None of that reduced her occasional capacity to induce a tug of wistfulness on his heart. Thoughts of her could still swallow him up for an afternoon or longer. He knew that it was pointless, and dreamy, but there were days when he felt helpless to do anything but ruminate in the memory of it.

The idea of hockey as a highly choreographed but expressive dance routine, capable of providing a stage for group and solo performance, had not been articulated in Morenz’s own time. However the roots of the thought were already percolating in the minds of everyone who attempted to draw meaning from the game’s patterns. Fans, writers, and even hockey executives were already noting the connection between dance and the style of hockey players who showed a superior ability to transfer their dance skills to the ice.

An actual ballet, Les Patineurs, was choreographed later in the decade, and first performed February 16, 1937, in London, England by the Sadler’s Wells Ballet. This ballet, set to the music of Giacomo Meyerbeer, was first performed in New York in the 1946 fall season. See Terry, Walter; Ballet, Dell Publishing Co., Inc. (New York: 1959), at pp.227 – 228. Russians already appreciated the association of games and ballet – as exemplified by the Nijinsky ballet, Jeux, based on the kind of dancing involved in tennis, which was first performed in Paris in May, 1913: Terry, Walter; Ballet, Dell Publishing Co., Inc. (New York: 1959), at p.180. Adam Bock’s own Five Flights, showing the congruence of ice hockey and Russian ballet, played in New York in early 2004.

Aurel Joliat’s skating was often spoken of as balletic; e.g., Eskanazi, Gerald; Hockey, Grosset & Dunlap (New York:1973), at p.59; McAllister, Ron; Hockey Stars Today and Yesterday, McClelland and Stewart Limited (Toronto:1950), at p.68.

The Rangers’ Frank Boucher: Fischler, Stan; Slapshot!, Grosset & Dunlap (New York: 1973), at p.27; and the Leafs’ Max Bentley: Batten, Jack, “The Best?†in Frayne, Trent, ed.; All-Stars: An Anthology of Canada’s Best Sportswriting, Doubleday Canada Limited (Toronto:1996), at pp.123, 126; were paid similar tribute. Even before Harvey “Busher†Jackson became a member of the Maple Leafs, Frank Selke waxed adoringly about him because he “was as light on his feet as a ballet dancer. He could pivot on a dime . . . .â€: Selke, Frank, with Green, H. Gordon; Behind the Cheering, McClelland and Stewart (Toronto:1962), at p.54

In time, through the work of men like Eddie Shore, and Lloyd Percival,[1] the relationship between the game and dance, and the recognition of the ability to dance as an essential hockey skill, would become accepted: Michener, James A.; Sports in America, Random House (New York:1976), at p.293 identified the play of goaltenders Ken Dryden and Bernie Parent as evocative of “the instantaneous beauty of great ballet.â€

Eddie Shore made efforts to include dance as part of hockey training, though his efforts in this regard have often been the subject of mockery: e.g., Fischler, Stan; Those were the Days, Dodd, Mead & Company (New York:1976), at pp.64 65; Cruise, David and Griffiths, Alison; Net Worth, Viking (Toronto:1991), at pp.179 – 180, who noted that in addition to tap dancing, Shore could get absorbed in teaching highly precise foot placements for improved skating. See also: Cherry, Don with Fischler, Stan; Grapes: A Vintage View of Hockey, Avon Books of Canada (Toronto:1982), at pp.107 – 108.

Lloyd Percival developed similar views, and his thoughts on the topic received a somewhat better reception: Percival, Lloyd; The Hockey Handbook, The Copp Clark Co. Limited (Toronto:1951), at pp.290 – 292. Interestingly the dances he references as suitable for training were dances from Morenz’s 1920s: the Charleston and the Black Bottom.

However the hockey establishment remained skeptical into the 1970s: Ludwig, Jack, “Team Canada in War and Peaceâ€, Maclean’s, December, 1972, in Benedict, Michael, and Jenish, D’Arcy, eds., Hockey on Ice: 50 Years of Great Hockey, Penguin Books (Toronto:1999), at pp.299 – 300.

The best hockey players, as physically accomplished athletes, would incorporate a superior ability to dance into their play: e.g., Fischler, Stan; Slapshot!, Grosset & Dunlap (New York: 1973), at p.27. See also: Michener, James A.; Sports in America, Random House (New York:1976), at p.80. That ability would eventually began to be appreciated for itself, and be recognized as an essential aspect of hockey expression and not simply as a supportive skill for the playing of the game: e.g., Paris, John, Jr., with Ashe, Robert; They Called me Chocolate Rocket, Formac Publishing Company Ltd. (Halifax:2014), at pp.101 – 102; Jeremiah, Eddie; Ice Hockey, The Ronald Press Company (New York:1942, 1958), at p.57; Fischler, Stan & Shirley; Everybody’s Hockey Book, Charles Scribner’s Sons (New York:1983), at p.xv.

By the time of the 1972 Summit Series, Canadian players and fans openly compared the best Russian hockey players to dancers, and even to the magnificent Rudolf Nureyev: Rudolf Nureyev, 1938 – 1993: Dryden, Ken, with Mulvoy, Mark; Face-Off at the Summit, Little, Brown & Company (Canada) Limited (Toronto:1973), at p.48. See also: Macskimming, Roy; Cold War: The Amazing Canada-Soviet Hockey Series of 1972, GreyStone Books (Vancouver, BC:1996), at p.102. It should not have beem a revelation. As Jim Coleman had observed in 1971, Howie Morenz had evoked the same kind of comparison to his nearer ballet contemporaries, Anna Pavlova (1881 – 1931) and Vaslav Nijinski (1889 – 1950).

Howie Morenz continued to be bewitched by dancing throughout his career, even as his playing days moved closer towards retirement. He enjoyed the community street dances when he visited home in the summers (Unidentified newspaper clipping from Stratford, “Community Dance at Mitchell Was A Decided Success,†August 12, 1933), and had thoughts about opening up a dance pavilion on the main road near Stratford as a retirement project: (Robinson, Dean; Howie Morenz: Hockey’s First Superstar, The Boston Mills Press (Erin, Ontario: 1982), at p.88).

He might even have lingered over a thought about whether Ruby Keeler, by then the famous woman on the silver screen, might find it in her heart to stop by. That kind of distracted thinking never got beyond fantasy, but it could serve to explain Howie’s off-night on hockey’s biggest stage.