Chicago and the Stadium

When the Canadiens traveled to Chicago in late 1930, they were traveling to a city that was recognized as “the most corrupt and lawless city in the world†[Fletcher Dobyns, The Underworld of American Politics, Fletcher Dobyns Publishing, 1932]. La Patrie (7 avril 1931, p.12, c2), was just as blunt. Chicago was “la ville des ‘gunmen.’â€

The Stadium was still impressive. Paddy Harmon, the one-time “corner newspaper boy†in a city of powerful, self-promoting men, had always been a little more ostentatious than his rivals – both in his dress and in the breadth of his vision. He did not just attract attention, he knew how to command it. He had yearned to bring the National Hockey League to Chicago, and wanted people to think of him as the â€Tex Rickard of the West.â€.

Harmon built The Stadium for a reputed $7,000,000, (or maybe $ 6 million) in hope: (Vass, George; The Chicago Black Hawks Story, Follett Publishing Company (Chicago:1970), at pp.18 – 19). Harmon then offered $50,000, or $51,000, about double the money offered by Major McLauchlin, for the city’s NHL franchise, but was turned down: Hewitt, Foster; Hockey Night in Canada: The Maple Leafs’ Story, The Ryerson Press (Toronto:1956), at p.73; Isaacs, Neil D., Checking Back: A History of the National Hockey League, W. W. Norton and Company, Inc. (New York:1977), at p.62.

It was his arena that the NHL and its owners found too magnificent to ignore.

By the time Harmon had been killed in a car accident in Chicago on July 22, 1930, he had lost control of the Stadium to the wealthy grain-dealer, James Norris.

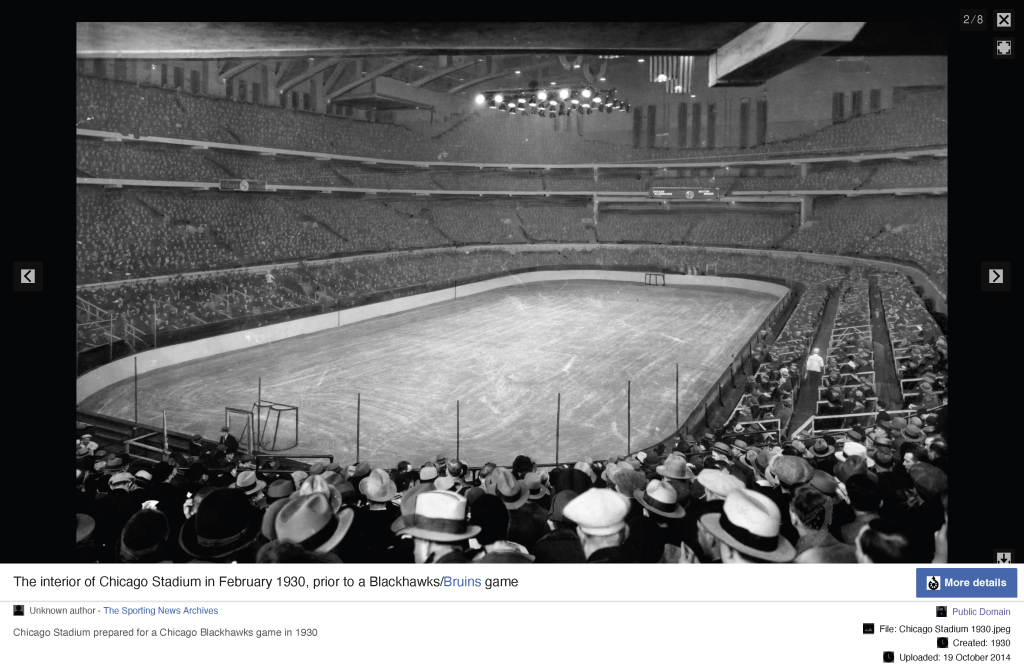

The Stadium was big enough that both grain-dealer James Norris and western prospects alike would see it and say “Boy, you could put lots of hay in hereâ€: Daniels, Calvin; Guts and Go: Great Saskatchewan Hockey Stories, Heritage House Publishing (Calgary, AB: 2004), at p.181. In terms of accommodating actual paying customers, it was the largest from the time it was built until it was replaced decades later. In the first Stanley Cup playoff series of 1931, McLaughlin had workmen continue to add seats to accommodate larger and larger audiences.

The fans could get so close that players could “feel that the fans are leaning right over your shoulder.†(Ferguson, John, with Fischler, Stan and Shirley; Thunder and Lightning, Prentice-Hall Canada, Inc. (Scarborough:1989), p.33). There were also no barriers separating the player benches from the fans, and the distance between the ice surface and the furthest seat was a mere 100 feet, a good egg or (gravity-assisted) bottle throw, away. (Cole, Stephen, The Last Hurrah, Penguin Books (Toronto:1995), at p.207).

Occasionally older fans pretend to wistfully recall the older NHL arenas as “meditative places sheltered from the swirl of the outside world,†and how:

You used to buy a ticket in hope of escaping the travails of real life, not to be boiled in hype. (Bidini, Dave, Tropic of Hockey: My Search for the Game in Unlikely Places, McClelland & Stewart Ltd. (Toronto:2000), at p.220)

If such a rink ever hosted an NHL game, it would never have been the Madhouse on Madison, either in the 1930s or later. Indeed, the Stadium’s hockey crowds were unique, and memorialized by poet Tom Clark (Clark, Tom; “Chicago†in At Malibu; quoted in Bowering, George; The Hockey Scribbler, ECW Press (Toronto:2016), at p.13. More than pennies and eggs regularly found their way to the ice surface:

It had been an adventure for high society the first time out, but the attraction began to pale. In later years the society that turned out was a different sort, to judge by the rotten eggs, dead fish, and even cherry bombs that were flung on the ice. . . . From the beginning life in the Stadium was just as much fun as games, . . . . (Vass, George; The Chicago Black Hawks Story, Follett Publishing Company (Chicago:1970), at p.20)

The experience of playing there, or the anticipation of playing there, could become intimidating in a different way than the Boston Garden. There was never any predicting what any one of those spectators, or all of them, might do – during or after a game – to friend or foe:

Watching a hockey game in Chicago is like watching the Christians against the Lions, except that in Chicago most of the animals are in the stands. (Gzowski, Peter, “The Maple Leaf Money Machineâ€, Maclean’s, March 21, 1964, in Benedict, Michael, and Jenish, D’Arcy, eds., Hockey on Ice: 50 Years of Great Hockey, Penguin Books (Toronto:1999), at p.27

Even a generation after Morenz, after his own career of playing games in all the NHL cities, Maurice Richard rated the paying inhabitants of The Stadium as the worst fans in the League:

The first and second balconies here don’t know much about hockey – all they do is make noise. (O’Brien, Andy; Rocket Richard, The Ryerson Press (Toronto: 1961), p.34)

We have not even begun to talk about the grand organ that supported the fans in creating such a “wall of noise†that visiting players could barely hear themselves breathe: (Dowbiggin, Bruce, The Defence Never Rests, HarperCollins Publishers Ltd (Toronto:1993), at p.142).

Referee Ron Finn recalled experiencing the Stadium in much the same way:

It is a building with a long history and it has fans who are able to make enough noise that you begin to think you’re inside a jet engine. The organ, of course, is the mainstay of the building and when the national anthems are played, I swear that the ice actually vibrates. Your whole body tingles and it’s like getting an electrical charge. Finn, Ron, with Boyd, David; On the Lines: The Adventures of a Linesman in the NHL, Rubicon Publishing Inc. (Oakville, Ontario:1993), at p.62.