Ethnicity: Benny Leonard and Howie Morenz

Philadelphia Quakers’ owner Benny Leonard knew how coded language could flare into explicit anti-semitism with one angry snort. Professionl hockey was not immune: e.g., Fischler, Stan; Slapshot!, Grosset & Dunlap (New York: 1973), at pp.101 – 112.

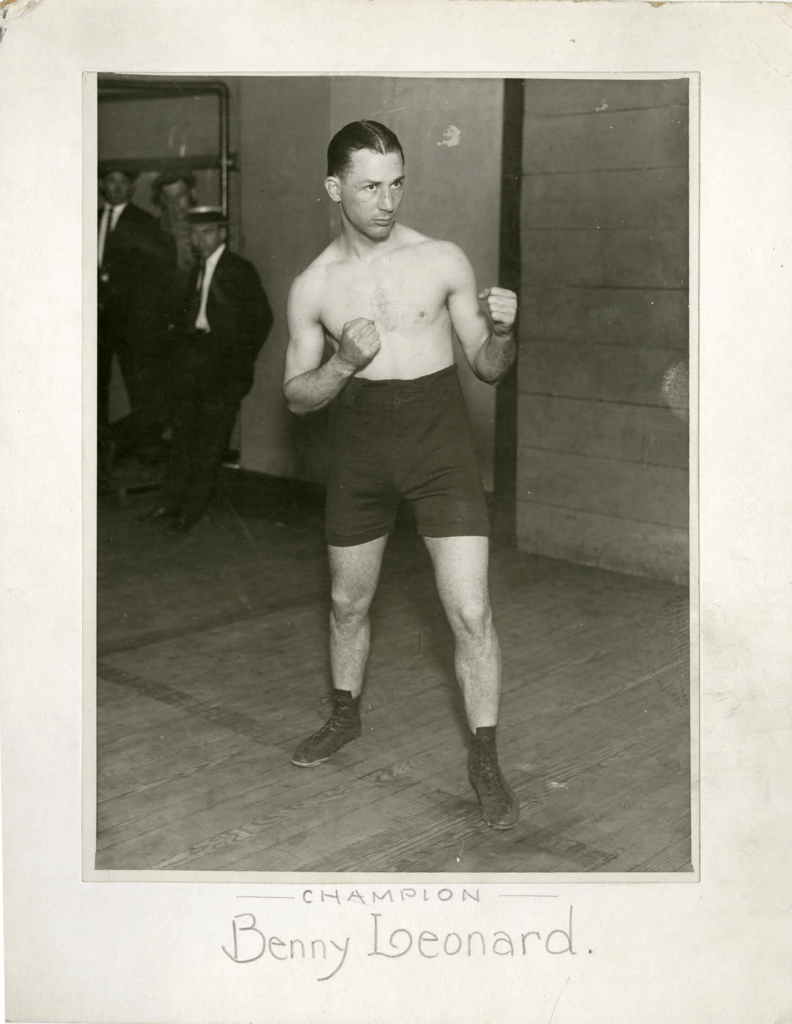

When he had first become a professional fighter, Benjamin Leiner had succumbed to pressure to change his last name to Leonard to protect his family from embarrassment, or identification. Many fight fans had simply known Leonard as “Ghetto Wizard” anyway. Former Canadiens’ owner, George Kendall, had taken the same path in Montreal. When he decided to become a prize-fighter to the horror of his Westmount family, he chose to do so using the name George Kennedy. For both, success in the ring eventually brought a measure of recognition and acceptance outside the ring.

Although Leonard’s status as a Jew became less of a barrier, and no longer needed to be a secret, Leonard’s change of name had not freed him from stereotype and racial judgment. In his first year of involvement with the NHL he was already too aware of the status barrier between him and some other owners. For the next half-century Conn Smythe would continue to sniff that a boxer from a “crooked” sport running a hockey team “was always good for a few laughs.”: Smythe, Conn, with Young, Scott; If You Can’t Beat ‘Em in the Alley, PaperJacks Ltd. (Markham, Ontario:1982), at pp.90, 117. Smythe didn’t choose to mention that the Quakers’ first ever win (of 4 in their entire existence) was against his Leafs on November 25, 1930.

Leonard wanted his players to play as if they resented every breath drawn by their opponents. He wanted other teams to worry about playing them, to see the prospect as distasteful, and certainly dangerous. It would be 42 years before another Philadelphia NHL hockey team would be baptized as “the Broad Street Bullies,” the moniker coined and published in the Philadelphia Bulletin on January 3, 1973: Kimelman, Adam, The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly Philadelphia Flyers, Triumph Books (Chicago:2008), at p.26. However Leonard’s essential idea of using violence as a way to succeed at hockey, and to attract fan support, was ahead of its time: Russell, Gordon W.; Aggression in the Sports World: A Social Psychological Perspective, Oxford University Press (New York:2008), at p.108.

Leonard’s idea was still squarely aimed at the public appetites of the day. As Paul Gallico explained:

I have always suspected that the real appeal of hockey, and the reason for its immediate success when introduced from Canada to American audiences in 1925, are that it is a fast, body-contact game played by men with clubs in their hands and knives lashed to their feet, since the skates are razor-sharp, and before the evening is over it is almost a certainty that someone will be hurt and will fleck the ice with a generous contribution of gore before he is led away to be hem-stitched together again. There is also an excellent chance of free-for-all before an evening’s exhibition is over, involving all the players of both teams and often including spectators as well as police, all swinging clubs, hockey sticks, and fists in merry riot. Cantankerous and short-tempered hockey-players are considered a great draw.: Gallico, Paul; Farewell to Sport, International Polygonics, Ltd. (New York:1990), at p.324.

Gallico made no secret that he disliked professional hockey: Gallico, Paul; Farewell to Sport, International Polygonics, Ltd. (New York:1990), at pp.323 – 324, and even resented the sham and shady amateur game as well: at pp.113, 120 – 121.

One can understand how Leonard believed that the turning point of the Quakers’ season had been at the Boston Garden on Christmas Day, 1930. Even though the Quakers had been outscored 8 – 0:

After the Boston Bruins piled up an eight-goal lead on the scoreless Philadelphia Quakers . . . , the latter dropped their sticks and engaged in a savage melee with their rivals.: The Montreal Daily Star, December 26, 1930, p.20, c.7

And just three days before the Canadiens arrived in Philadelphia, the Quakers had beaten the Montreal Maroons at the Philadelphia Arena for their second win in three months of League play. Violence, and a violent attitude, had begun to show rewards.

Benny Leonard’s team began their game against the Canadiens with aggression:

Des le commencement des hostilites, les portes-couleurs du Philadelphie s’appliquerent a “checker” et malmener leurs adversaires, . . . .: La presse, 14 janvier 1931, p.24, c.4

A wary start by the Canadiens turned to surprise just three minutes in when Quaker defenceman Allan Shields upended Joliat, stripped him of the puck, and then stickhandled on a solo rush towards the Canadiens’ end of the ice:

. . . and great credit must be given to Al for the cool and collected manner in which he did the work. After cleverly dribbling through the “Flying Frog” defense, he found himself clear ten feet from the goal. Instead of shooting wildly, he carefully measured his shot and skimmed it six inches off the ground over Hainsworth’s outstretched leg.: The Philadelphia Inquirer, January 14, 1931, p.19, c.1 – 2.

Shortly after that opening score, Al Shields took Howie Morenz down in front of the Philadelphia net – giving Morenz his five inch gash above his right eye. Shields received a major penalty for what the referees called a “trip.” Before Morenz had even made his way under the stands for stitching and a bandage, Johnny Gagnon became tangled with “Peaches” Lyons, and the two “tried to decapitate each other with their sticks.”: The Philadelphia Inquirer, January 14, 1931, p.19, c.1. Gagnon had already earned a Philadelphia reputation during his time in the Can-Am league as:

. . . another half-pint Frenchman full of the fire that captivates. When playing against the Arrows he was always in trouble – starting fights: The Philadelphia Inquirer, December 3, 1930, p.16, c.4

Lyons and Gagnon joined Shields in the penalty bench with their own major penalties as the game continued to be:

. . . marred . . . by the belligerence of the Quaker defence. . . . the majority of the rough stuff was done by [D’arcy] Coulson who went after his man every time and usually made a good job of it.: The Gazette, January 14, 1931, p.16, c.3

Coulson continued his sturdy body checking . . . and the manner in which he slowed Joliat and Morenz was a lesson to other defense men: The Philadelphia Inquirer, January 14, 1931, p.19, c.1

The kind of aggressive chippiness that Howie Morenz had endured during his first visit to the city in early December had by January become a Quaker ethos of resentful and defiant violence. It now seemed swollen with disregard for any visitor’s physical safety:

The Flying Frenchmen of Montreal found . . . that the small ice of the local Arena is just about the toughest place to play in, and finally they uncovered the reason for the alarming parade of major penalties that has followed in the wake of the fighting Quakers.: The Gazette, January 14, 1931, p.16, c.3

The game was developing exactly the way Leonard hoped might sell tickets, and create more success for his team.

When Howie Morenz returned to the ice, wiser now by the several new stitches across his forehead, he and the Canadiens responded to the Quakers in kind:

The Quaker defense men started out by slapping Joliat and Morenz to the ice with fierce body checks. This was something the stars of the visitors did not relish and they uncorked a sneaky yet clever club slashing and skate cutting retaliation: The Philadelphia Inquirer, January 14, 1931, p.19, c.1

For 33 minutes . . . the Quakers held a 1 – 0 advantage and in this time gave the Canadiens more than they received in return: Philadelphia Daily News, January 14, 1931, p.36, c.5 – 6

The referees . . . allowed the underhanded work to continue throughout the game: The Philadelphia Inquirer, January 14, 1931, p.19, c.1

The abrasive conflict among the players remained as genuine as it was bitter and, as Gallico had predicted, it thrilled the fans: The Philadelphia Inquirer, January 14, 1931, p.19, c.1 – 2

Howie’s willingness to tolerate the provocative behaviours of opponents had already become an accepted truth around the league – based on the “Hec Kilrea incident” as related by Elmer Ferguson in Montreal Herald, December 20, 1950:

In one of his streaking rushes, he [Morenz] cut sharply across in front of Hec Kilrea, sturdy Ottawa right wing, and roughed up Kilrea in the process. Kilrea, a very clean and sporting player himself, temporarily lost control, and whacked Morenz sharply over the head with his stick.

Morenz tumbled to the ice, knocked out, while Kilrea stood aghast at the result of a gesture that was entirely instinctive. Morenz was carried off, stretched out on a table in the dressing-room. A few minutes later, he opened his eyes, blinked, but instead of denouncing his attacker, he said, boyishly: “I don’t think Hec meant it. Do you?”’

Morenz was like that.

A slightly different version of the story appeared in Frayne, Trent; “How they broke the heart of Howie Morenz”, MacLean’s Magazine (October, 1953), p.27, c.2, reprinted in Benedict, Michael, and Jenish, D’Arcy, eds., Hockey on Ice: 50 Years of Great Hockey, Penguin Books (Toronto:1999), at pp.63- 72, and Frayne, Trent; Famous Hockey Players, Dodd, Mead & Company (New York:1973), pp.14 – 15. A different one again appears in Robinson, Dean; Howie Morenz: Hockey’s First Superstar, The Boston Mills Press (Erin, Ontario:1982), at pp.79 – 80. Versions of the story were also repeated in Sullivan, George, Face-off: A Guide to Modern Ice Hockey, D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc. (New York:1968), p.117, and in Fischler, Stan; Those were the Days, Dodd, Mead & Company (New York:1976), at p.82

Morenz made his presence known within the cramped ice surface of the Philadelphia Arena:

. . . even in the tough going, they were led by the dashing Morenz . . . . The Stratford flash worked like lightning in the first period only to see Allan Shields . . . beat Hainsworth on a hard one to the far corner.

But Morenz kept going, . . . . The Gazette, January 14, 1931, p.16, c.3

Morenz’s apparent lack of a physical response to the Kilrea clubbing, and the absence of any overt violence in response to this night’s provocations from Shields’ slash and other abrasions, represented a conscious choice to reject the kind of belligerence encouraged by Leonard. While Leonard’s sport easily led him to expressing himself through fistic intimidation with an attitude of retribution, Howie Morenz made an intentional effort to turn away from that aspect of hockey.

Morenz’s unassisted goal to tie the game came with less than 5 minutes remaining in the second period, and the Quakers managed to delay and re-direct the Canadiens’ attack for the balance of the middle session:

The Quaker body checks were getting weaker and weaker as the period wore on, but Forbes continued to do his work adequately and the best Canadiens could do was tie the count.: The Gazette, January 14, 1931, p.16, c.3; La presse, 14 janvier 1931, p.24, c.4

However from the start of the third period it was clear that the Quakers’ effort to manhandle the Canadiens during the first 40 minutes had exhausted them. Morenz continued to inject momentum into the Canadiens’ offence:

The Canadiens showed so much speed that the Quakers, in trying to cope with it wore themselves out after two periods and appeared as though they were standing still in comparison with the sleek skating of the Canucks in the final period.: The Montreal Daily Star, January 14, 1931, p.26, c.7

Before the Quakers could manage even a single shot on Hainsworth in the third, Morenz had put the Canadiens a goal up:

The Flying Frenchmen unleashed as terrific an attack as possible on the small surface as the third session began and after six minutes of scoreless pounding at Forbes, Morenz dashed from the centre, passed neatly to Wasnie as he crossed the blue line, and the right winger burned home a terrific shot that Forbes tried to stop with his skate but failed. It sped true to the far corner for the winning tally.: The Gazette, January 14, 1931, p.16, c.3.

Morenz came flying down the ice, dribbling over the blue line, and then passed at the proper moment to Wasnie. Forbes was off balance as Wasnie shot and the low puck went into the net.: Philadelphia Daily News, January 14, 1931, p.36, c.6

Howie Morenz had not only created the whole of the Canadiens’ offence, nearly single-handedly, but he had done it so deftly that he didn’t take a penalty against a team with a defence that was committed to causing him actual harm.

Benny Leonard felt a pinch of frustration, discovering that his players were not physically capable of keeping pace with the Canadiens for 60 minutes, even though his defence corps had bullied the speeding Frenchmen to a standstill for more than half the game. Morenz and the rest of the Canadiens had churned against the provocative grime of the Quakers’ harassment and then calmly moved the game to a level that the Quakers couldn’t reach.

It had been an intimate performance. The Arena may have had as few as 3,000 fans in attendance to see Morenz and the rest of the champions: La presse, 14 janvier 1931, p.24, c.4; The Gazette, January 14, 1931, p.16, c.3. Other reports were more generous: The Montreal Daily Star, January 14, 1931, p.26, c.7 – 8 reported 3500 fans, and The Philadelphia Inquirer, January 14, 1931, p.19, c.1 reported 4000.

Nevertheless those who were there were able to appreciate what they had just witnessed:

Les amateurs de hockey de Philadelphie doivent se dire qu’ils ont ete temoins hier soir de la meilleure partie jamais joue chez eux.: La presse, 14 janvier 1931, p.24, c.5

It hadn’t been the best game of the year because of the violence. It had been the best game because Howie Morenz had shrugged off the provocations and the five inches of stitches across the forehead, to play his best game.

There were still some in Philadelphia who focused only on the scoreboard result, and resentfully disparaged the successful Canadiens as “Flying Frogs,”: The Philadelphia Inquirer, January 14, 1931, p.19, c.1 – 2. Then, in half-apology for disparaging Morenz and his club as foreign strangers, the Daily News reflected:

Surely an athlete doesn’t have to be on the home club to be appreciated in hockey. Babe Ruth pleases even when he hits a homer to down the Athletics. And why shouldn’t the spectators thrill to a solo flight by Morenz or Joliat while defeating the Quakers?: Philadelphia Daily News, January 13, 1931, p.31, c.4

But echoes of the same racial/cultural/lingual prejudice remained into the 1970s, when the repetitively triumphant Canadiens were still classified and dismissed as “Gorfs”: in Liss, Howard; Goal! Hockey’s Stanley Cup Playoffs; Delacorte Press (New York: 1970), at p.180.

Leonard’s own acceptance in Philadelphia remained conditional. Perhaps any love in Philadelphia would have remained conditional because Leonard had once recused himself into a no-decision against local hero Lew Tendler: Liebling, A. J,; The Sweet Science, Grove Press Inc. (New York:1956), at pp.92 – 93.

Now he was in a situation where interest in his Philadelphia hockey team was evaporating quickly: Laroche, Stephen; Changing the Game: A History of NHL Expansion, ECW Press (Toronto:2014), at p.30; McFarlane, Brian; Legendary Stanley Cup Stories, Fenn Publishing Company Ltd. (Bolton, Ont.:2008), at p.63.

He was seen, perhaps, as either Bill Dwyer’s protégé: Laroche, Stephen; Changing the Game: A History of NHL Expansion, ECW Press (Toronto:2014), at p.30; McFarlane, Brian; Legendary Stanley Cup Stories, Fenn Publishing Company Ltd. (Bolton, Ont.:2008), at p.63; or Bill Dwyer’s nominee: Eskanazi, Gerald; Hockey, Grosset & Dunlap (New York:1973), at p.28.

To seek a real answer to those questions would require some accurate knowledge, perhaps now unattainable, about who was paying New York attorney Joseph Shalluck, who was described as responsible for transferring responsibility for player contracts from Frank Frederickson of the Pittsburgh Pirates to Benny Leonard’s Quakers: The Montreal Daily Star, October 21, 1930, p.26, c.6; and who James P. Callaghan was speaking for as “president” of the club when the move from Pittsburgh to Philadelphia had been announced: La presse, 14 octobre 1930, p.24, c.7.

In the absence of an answer to those questions, it could simply be that anti-semitism played a role in the failure of the Quakers within the National Hockey League as it had in the success of Leonard’s fight career. The whiff of anti-semitism in National Hockey League circles has certainly been observed since: e.g., Klein, Jeff Z., and Reif, Karl-Eric, The Death of Hockey, MacMillan Canada (Toronto:1998), at pp.139 – 140; Fischler, Stan; Slapshot!, Grosset & Dunlap (New York:1973), at pp.93 – 112.

The only certainty for Leonard was that Philadelphia had become a financially and emotionally impoverishing hockey experience for him: Eskanazi, Gerald; Hockey, Grosset & Dunlap (New York:1973), at p.28; McGowen, Lloyd, “Hockey’s Cooper Smeaton Earned Accolades,” in The Montreal Star, December 9, 1961, p.24. Violence had not turned out to be the solution to his hockey problems.