Howie Morenz and the Flying Game

“Flying Frenchmen” True to the Name –

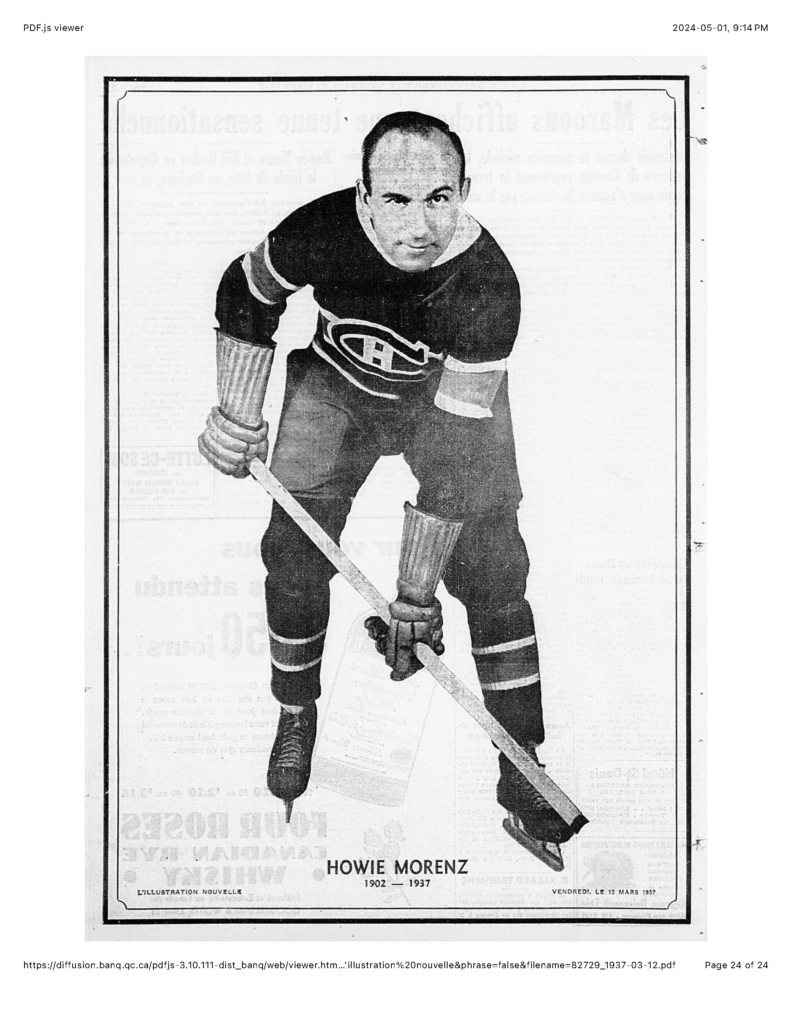

Morenz was always a glamorous figure. No one who saw him could ever forget him. Those were the days when Canadiens were almost more than a hockey team, something of the symbol of the dash and gallantry of a race, and to watch the magnificent Morenz leading the great line of Morenz, Joliat and Gagnon like a red wave to the enemy’s goalposts was an unforgettable experience.- Mike Rodden, The Globe, January 12, 1931, p.10, c.3 – 4

When Leo Dandurand let it be known that he was on his way to Providence to look at players, he did not mince words about what the Canadiens needed – a defenceman, a couple of left wingers, and a centre who could play left wing. There were three players there who might fit those needs: Defenceman Art Lesieur, and forwards Leo Gaudreault, Gizzy Hart, and Bud Cook.

The Canadiens did need more from the left side of the offence. Aurel Joliat had one goal in the team’s previous 8 games. Armand Mondou had not registered a point in nearly a month. In fact Mondou had been so uninvolved that he hadn’t even taken a penalty all season long. The defence was small, and an injury away from being inadequate.

When Bobby Hewtison dropped the puck between Howie Morenz and Andy Blair at 8:30 on Saturday evening, and the Canadiens broke from the face-off with an impatient snap, and it was Canadiens ahead 1 – 0 over the Leafs 15 seconds later:

Le Canadien n’a pas tarde pour se mettre a l’oeuvre . . . . Les dernier notes de l’hymne national resonnaient encore que Howie Morenz s’emparait de la rondelle a sa mis au jeu par l’arbitre Bobby Hewitson et se dirigeait promptement vers la fortresse du Toronto. Alors que tous s’attendaient a le voir tirer selon son habitude, Howie fit une passe rapide a Johnny Gagnon qui tira aussitot pour loger la rondelle dans le filet des visiteurs au milieu d’une acclamation qui ebranla le Forum.: La presse, le 12 janvier, 1931, p.18, c.1

A three-man rush led down centre by Morenz saw Johnny Gagnon complete the play. Johnny accepted Morenz’s pass to right wing perfectly to swing in on a helpless Chabot. Gagnon curved right up to the goal-mouth. He stick-handled the Toronto goalie out of his cage, and flipped the puck home with a back-hand twist with Chabot prone on the ice: The Gazette, January 12, 1931, p.18, c.1.

The Canadiens’ pace mesmerized the Leafs:

Snapping out of their recent slump with a display that was neat and gaudy and gleamed with sparkling plays they smothered the white gowned invaders by sheer speed, throttled their thrusts with great backchecking; and riddled their defensive with a swooping attack that knew no let up: The Montreal Daily Star, January 12, 1931, p.20, c.1 – 2

They flashed over the Forum ice at a tremendous clip on Saturday night, as if they thoroughly enjoyed the pace and shaking off of the mental and physical slump that had enveloped them in varying degrees for about a month.: The Gazette, January 12, 1931, p.18, c.3.

This was already Howie Morenz’s kind of game. Fast skating. Up the ice, back, up the ice again. Glide in on the defence, flutter in front of the net, dive towards the goal, and then pursue the puck again before making a turn back towards the opponent’s net. It was breathtaking.

Howie Morenz and the Canadiens found themselves playing a league game with the same kind of natural enthusiasm and verve, the same kind of tireless and reckless unconcern, that was usually the preserve of eight year olds on lake or river ice. They were liberated from any concern about scoring or winning, and even the fear of losing. They felt utterly unbeatable.

This was the best kind of game that Howie Morenz, and his Canadiesns, could play. It was a game in which he and his teammates would vault each other, toward greater and greater velocity. Playing this way, they encouraged each other to re-imagine opportunities to score at each moment. It was how Morenz played in the first period of his very last game. Hugh McLennan recalled him on that last night, as Morenz continued to experience that true delight of playing the game at its highest level:. Morenz was fully infused then with his:

. . . rare combination of speed, power and gentleness, and there was something in his style that made everyone love him. I was in the Forum that January night . . . . He had been playing marvelously that evening and the little smile on his lips showed that he was having a wonderful time: MacLennan, Hugh, “Fury on Ice”, in Gowdey, David; Riding on the Roar of the Crowd: A Hockey Anthology, Macmillan of Canada (Toronto:1989), p.10.

That excitement about playing the game at this kind of level was infectious and demanding.

Morenz remained the standard against which the rest of the Canadiens were being measured, but tonight each of them were chasing close enough behind that the team game levitated:

Morenz a encore ete le plus rapide de tous mais ses compagnons ne lui ont pas ete beaucoup inferieure et ont merite plus que jamais leur surnom de “Flying Frenchmen.”: La Presse, 12 janvier 1931, p.18, c.1

This amplified game being played by the Canadiens provided a fascinating vision of how the game could be played. Toe Blake would describe that kind of complementary speed as the essence of the game, the ideal:

Le hockey est un jeu si rapide qu’il exige une synchronization parfait; il faut que tous les joueurs travaillent en parfait harmonie pour compter des buts et ganger des joutes.: Blake, Toe; Le Hockey, pamphlet, The Ralston-Purina Company of Canada Limited, Ganes Productions Limited (Toronto:1963), at p.12

It was also what Marshall McLuhan would identify as demonstrating the game’s inherent edifying quality:

. . . . . it is the pattern of a game that gives it relevance to our inner lives, . . . not who is playing nor the outcome . . : McLuhan, Marshall; Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, 2nd edition, Signet Books (New York:1966), at p.214

The synchronicity and harmony that Toe Blake aspired to for his own teams grew out of games like these – when the Canadiens would soar as high as their fastest players, as high as Morenz, and everyone else on the team was caught in that same updraft. When it worked, when the Canadiens committed themselves to that kind of energy, it took the team to a level above imagination – to the thrill of creation.

The Gagnon goal in the third period reinforced something else that the box score readers often missed about the higher values involved in how Morenz pushed his teammates to play the game. The ability of Morenz to show off his full talents and the full scope of his game required teammates who had the skills to not only play with him, and at his speed, but also teammates who had the ability to blossom into the opportunities that he offered them – as Gagnon did twice on this Saturday night at the Forum.

When fans saw Bobby Hull a generation later, people would point out that Hull was so fast that he often left his wingers behind – leaving no one available to take a pass: O’Brien, Andy; Superstars: Hockey’s Greatest Players, McGraw-Hill Ryerson (Toronto:1973), p.77.

A generation or more after Hull, Mark Messier would say the same about Wayne Gretzky:

He needs to be with players who can do something, and do things for him . . . Meisel, Barry; Losing the Edge: The Rise and Fall of the Stanley Cup Champion New York Rangers, Simon & Schuster (New York:1995), at p.251.

The same observation had been made about the need of Bobby Orr for players who could play with him: Dryden, Ken; The Game, Macmillan of Canada (Toronto:1983), at p.104. .

The way that Morenz was on his best nights was how Bobby Hull, Bobby Orr, and Wayne Gretzky too were on their best nights. Their best demanded that their teammates were called upon to play up, and to keep up, with the liberated magnificence of how they could perform.

Morenz had started the night hoping to help showcase how his Stanley Cup teammates could still play a dominating game together. As the last seconds ticked off the clock, the Forum crowd’s voice rose in praise and “unctuous satisfaction.”:The Gazette, January 12, 1931, p.18, c.1. Even The Globe acknowledged:

The ever-brilliant Morenz, Joliat and Gagnon were the premier performers for the winners with Lepine, George Mantha and Mondou pressing them hard for the honors: The Globe, January 12, 1931, p.10, c.2

Morenz himself remained a little in awe at how the Canadiens’ natural game, his own innate game, could so thoroughly dominate some of the best professional players in the world:

Toronto continue a attaquer et Canadien leur repond du tic au tac: c’est une des plus belles joutes encore vues cette annee sur la glace du Forum. Le petit journal, 11 janvier 1931, p.19, c.2.

Years later, Scotty Bowman would remark on the same quality of the best team he ever coached:

. . .All the games where we won Cups . . every time you saw the puck, if the other team was chasing it or coming out of their own end with it, there’s one of our guys right there. And then once they beat our guy and move the puck to another guy, there’s our guy there. We had speed on the forecheck, and our defence, as soon as the other team made a pass, a guy was right on him. They had no time and space. I mean when you can skate fast enough and always have someone pursuing the puck, the other team can’t get going. It’s because we had that speed.: Dryden Ken; Scotty: A Hockey Life, McClelland & Stewart (Toronto:2019), at p.362

Morenz and the Canadiens at their best in 1931 were playing the same game that Bowman’s Canadiens were playing in the last half of the 1970s.

Howie Morenz had demonstrated his ability to impose his own character onto the team: the ability to win, with both flourish and elan, at airborne speed. He had shown his team how to be more magnificent by adopting his own approach to the game.

While Howie Morenz wondered how this group in the dressing room could ever be any better, there were thousands still leaving the Forum who were thinking something else:

He was probably the greatest reason why Montreal Canadiens came to be known as the Fabulous Frenchmen, and why he was rated as the greatest of them all: The Stratford Beacon-Herald, December 27, 1950, p.14, c.8

The defining qualities of his play became the defining qualities of his team’s best play. He had made his best style the enduring touchstone of his team’s character: Whitson, David, and Gruneau, Richard; Artificial Ice: Hockey, Culture, and Commerce, Broadview Press (Toronto:2006), at pp.210 – 211.

Toronto 1 at Canadiens 6

Lineups

Canadiens Starters: Hainsworth, S. Mantha, Burke, Morenz, Gagnon, Joliat

Canadiens Subs: Mondou, Wasnie, McCaffrey, Larochelle, Leduc, Lepine, G Mantha, Rivers, Pusie

Toronto Starters: Chabot, Day, Clancy, Blair, Bailey, Cotton

Americans Subs: Jackson, Duncan, Horner, Jenkins, Primeau, Conacher

Referees: Bobby Hewitson, Eusebe Daigneault

First Period

1. Canadiens Gagnon (Morenz) 00:15

Penalties: None

Second Period

2. Canadiens Joliat 10:35

3. Canadiens Burke (Lepine, Gagnon) 13:45

4. Toronto Conacher (Jackson) 19:20

Penalties: Jenkins (scragging); Larochelle (scragging)

Third Period

5. Canadiens Gagnon (Joliat) 01:45

6. Canadiens G. Mantha (Rivers) 04:35

7. Canadiens G. Mantha 07:25

Penalties: Mondou (tripping); Leduc (high stick); Jenkins (tripping)