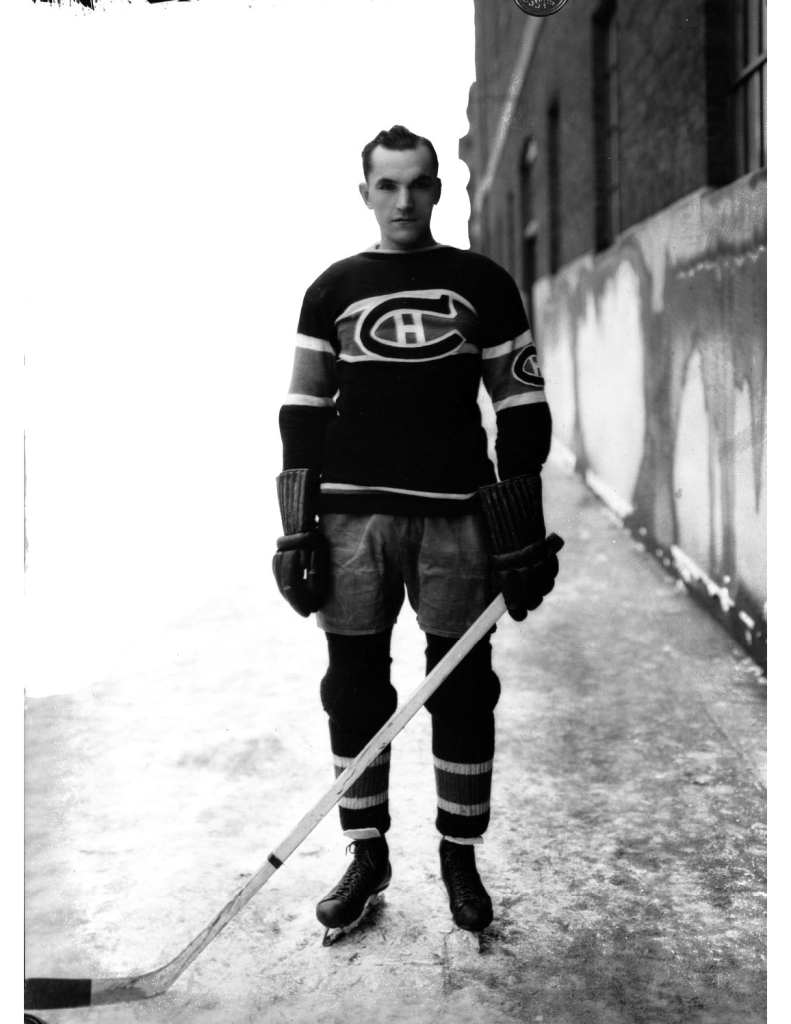

Physical Realities: Howie Morenz and Nick Wasnie

Before the phrase had become common, Morenz was referred to as the Canadiens’ “iron man†for his persistently physical style of play. In the playoffs of March 1930 against Chicago, The Gazette described him as follows:

Howie Morenz, the star of the game, was suffering from a slight charleyhorse yesterday, but will be on hand tonight. His superb physical condition made him the “iron man†of the game on Wednesday and he is expected to be the mainstay of the Frenchmen’s attack tonight. (The Gazette, March 27, 1930, p.17, c.3)

At the age of 28, Morenz still boasted a physique that was almost ideally suited to the hockey of his time. He stood 5’9â€, which was “above average height,†(Hewitt, Foster; Hello Canada! and Hockey Fans in the United States, Thomas Allen Limited (Toronto:1950), at p.38), and played at about 165 pounds, which was a little lighter than average (Robinson, Dean, Howie Morenz: Hockey’s First Superstar, Boston Mills Press (Erin, Ontario: 1982), at p.73).

The Forum Magazine, for January 16, 1926, pegged his weight that year at 160 pounds; the Forum Official Program for December 29, 1929, had bumped that up to 164.He was the same height and approximate heft as Stan Mikita – once described incorrectly as “the smallest N.H.L. player to lead the league in scoring.†(Eskenazi, Gerald; The Thinking Man’s Guide to Pro Hockey, E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc. (New York:1976), at p.34; Fischler, Stan; Those were the Days, Dodd, Mead & Company (New York:1976), at p.78).

Howie’s father acknowledged that later in his son’s career, by the 1935 – 1936 season, Howie’s weight had inflated to 181 pounds (The Stratford Beacon-Herald, January 29, 1937, p.10, c.1). By then Howie himself had recognized that the extra weight as an impediment to playing at his best. (Percival, Lloyd; The Hockey Handbook, The Copp Clark Co. Ltd. (Toronto:1951), p.310).

It wasn’t so much his size that made him unique, but his apparent endurance, or indefatigability, which gave him an edge against opponents over the course of a game. Ken Campbell explained:

Morenz was a 45-60-minute-per-game player and when teammates and opponents began to fatigue halfway through the game, Morenz had the stamina and conditioning to continue playing at an elevated level. (Campbell, Ken; “Howie Morenz†in A Century of Montreal Canadiens, The Hockey News Magazine, Transcontinental Media G.P. (Owen Sound, Ont.:1999), at p.27)

Charles Mayer recognized that same aspect of Howie’s game:

En outre, il ne cessait un seul moment de patiner apres la rondelle. Dans le temps, on jouait 60 minutes ou a peu pres. Plusieurs se dirent qu’a son allure ainsi qu’avec son esprit combatif qui ne lui laissant jamais un moment de repit, Morenz ne durerait pas bien longtemps dans la ligue Nationale. Toutefois, saison apres saison, Morenz continua a la meme allure, a la meme vitesse vertigineuse, au meme esprit combatif. (Mayer, Charles; L’Epopee des Canadiens de Georges Vezina a Maurice Richard, published by Charles Mayer (Ottawa:1949), p.79)

When the Americans’ “veteran of veterans†(The Gazette, December 15, 1930, p.24, c.1), Billy Burch, scored an unlikely goal near the mid-point of the second period to give the visitors a 1 – 0 lead in that December 13 game, Nick Wasnie began to be given a more regular turn at right wing.

Wasnie was physically similar to Morenz, though slightly larger at 5’10â€, and about 10 pounds heavier. He had arrived at camp in October at 172 pounds. (La presse, 21 octobre 1930, p.23, c.7 – 8).

About 2 years younger than Morenz, Wasnie was strong: a farmer from a family of farmers who lived north of Winnipeg. The Montreal Daily Star, April 1, 1930, p.28, c.2 described him as the owner of a grain farm. The Gazette, April 15, 1931, p.17, c.7 and The Globe, April 16, 1931, p.11, c.4, both reported that he owned a vegetable farm with his brothers.

His main value as a hockey player had become his ability to be a solid, defensive forward. He could endure the rough going in close-checkiing games without taking a lot of penalties, while still retaining some touch around the net. Those steady skills carried Wasnie from the rinks of Selkirk and Winnipeg to the NHL He played briefly with Chicago in 1927 – 1928 before returning to the minors. In his first full season with the Canadiens (1929 – 1930), Nick Wasnie scored 12 goals with 11 assists and had 64 minutes in penalties during the 44 regular season games. He added 2 goals, 2 assists, and 12 minutes in penalties in the 6 playoff games. In his final season with the Canadiens (1931 -1932) he had a hat-trick in a 5 – 2 victory over the Maroons (The Globe, November 18, 1931, p.8, c.5).

Unlike Howie Morenz who defined himself as a hockey player, Nick Wasnie’s relationship with the professional game was more practical. From the time he entered the league, he had attracted attention as being a little different – happy to defy the “hoodoo†by wearing the number 13 when he joined the Hawks in 1927 (New York Daily News; Sunday News, December 25, 1927, p.45, c.5).

He faced some social ostracism for his Polish ancestry in Montreal (noted by The Gazette, April 15, 1931, p.17, c.1), and was sometimes referred to as “le Polonais†in Le Petit Journal, 22 mars 1931, p.25, c.1. The Boston Globe, April 4, 1930, p.30, c.3, referred to him as an “ex-European,†perhaps in an effort to spread the idea that he was an immigrant, or displaced person. He was also one of two players on the Canadiens that The Gazette would snidely categorize as “dark visagedâ€: The Gazette, February 20, 1931, p.18, c.3.

Some sources suggest the real spelling of his name was Nickolas Waesne, but that was not used during any part of his professional hockey playing career, nor after.

The accumulation of these sotto-voiced slights doubtless leavened some of the grit that existed in his game. It may also have encouraged him to treat the professional hockey experience with some detachment. After winning the Cup with the Canadiens in the spring of 1930, he stuck around for a weekend before heading home to Manitoba with Gus Rivers while his teammates engaged in nearly a month of victory celebrations around the city, and did that exhibition series in Atlantic City. When the Canadiens of 1930 held reunions for exhibition games during the second world war, Nick Wasnie did not join them for those either: e.g., The Gazette, February 17, 1942, p.16, c.6 – 7. Perhaps the geographical distance was too large, but it could have been emotional as well.

Professional hockey became little more than a source of income to support Wasnie’s farming business while he played in the NHL, and a supplemental source of income when he played minor pro hockey in the American Hockey Association after his last NHL games in 1935. If there was any actual love of the game, that was secondary to his responsibility for earning a living – either as a farmer in Selkirk, or later as a grocer in Brainerd, Minnesota (The Minneapolis Star, March 13, 1935, p.16, c.2)

Nick Wasnie’s third goal of this season, and his second in two games, drew lukewarm reaction from the media:

Nick Wasnie is also developing his form of last year. Wasnie is a notoriously slow starter and hasn’t reached his stride yet, but those who noted his play in the Stanley Cup play-offs last spring, know that the right winger is a hockey player of stellar qualities when he is ‘right’ (The Gazette, December 15, 1930, p.24, c.3)

The men who played with and against Nick Wasnie had a better appreciation of the special qualities in his game. The sharp thrash of his stick was one of his unique talents:

Ask John Ross Roach who has the hardest shot in hockey and he’ll probably answer, “Nick Wasnie.†The Canadien right winger rarely makes a mistake around the goals and when he leans on the puck, it travels like a bullet. . . . He skates fast and hits hard (The Gazette, April 15, 1931, p.17, c.7).

When Nick Wasnie first joined the Canadiens, Aurel Joliat was assigned to teach him some of the particularities of the professional game (The Montreal Daily Star, March 11, 1931, p.26, c.2). Joliat came away from that work claiming that Nick Wasnie actually “invented†the slap shot (http://mbhockeyhalloffame.ca/people/nick-wasnie/).

It is also reported at http://ourhistory.canadiens.com/player/Nick-Wasnie that Wasnie attributed the power of his shot to a slight curve in the blade of his stick.

There was no recklessness to Nick Wasnie’s game. He played each shift that was given to him with diligence, abrasiveness, and an exertion of will. He devoted himself to the completion of assigned tasks, with no yearning to create or to live up to an expectation of dazzling excitement for the fans. His style of play could control important moments of a game. He could achieve that by physical attitude just as much as Morenz could control some games through speed and delight.

There was an impact to Wasnie’s career from that. He was seen as a cog, a utility player, rather than someone exceptional or unique (The Gazette, October 26, 1932, p.12, c.1). As a cog, he eventually had more value to the Canadiens in the trade market than as a roster player, and he would fit in well as a role player with these same New York Americans, and then the Ottawa Senators, and finally the St. Louis Eagles, between 1932 and 1935. He kept his body fit enough to play professional hockey until the spring of 1940, suiting up with Minneapolis (CHL Millers), Pittsburgh (IHL Shamrocks), and a final four years of professional hockey in Kansas City with the AHA Greyhounds. In all, he had played 15 years of professional hockey beginning with the Winnipeg Maroons.

Despite living his whole career with a cardiomyopathy, he ultimately lived longer than all of his Canadien teammates. Nick Wasnie passed away at the age of 86 on May 26, 1991. His next longest lived teammate was Georges Mantha, who died January 25, 1990: The Gazette, January 26, 1990, p.F6, c.2 – 4